PIE Audit Reform: When Public Interest Entities Fall Outside UK Definitions

Expert analysis of UK PIE audit reform proposals and the Baglan Bay case study. How current Public Interest Entity definitions miss systemically important companies.

Author: Dean Beale, Executive Director for the Centre for Public Interest Audit

Follow us or get in touch to join the conversation.

Current UK Public Interest Entity Law and Limitations

In UK company law, a Public Interest Entity (PIE) represents companies requiring enhanced audit quality standards and regulatory oversight. PIEs have a systemic importance to capital markets and public interest. Section 494A of the Companies Act 2006, which implemented an EU Audit Directive, sets out three categories of PIE:

(a) issuers whose transferable securities trade on a UK‑regulated market

(b) credit institutions such as banks

(c) insurance undertakings

The logic is clear: a sudden failure in any of these sectors could undermine confidence in capital markets, jeopardise depositors’ money, or impact policy‑holders. However, restricting the label to those statutory buckets leaves many large private companies outside the net; companies that may employ thousands of workers or provide essential services.

Post‑Carillion Soul‑Searching

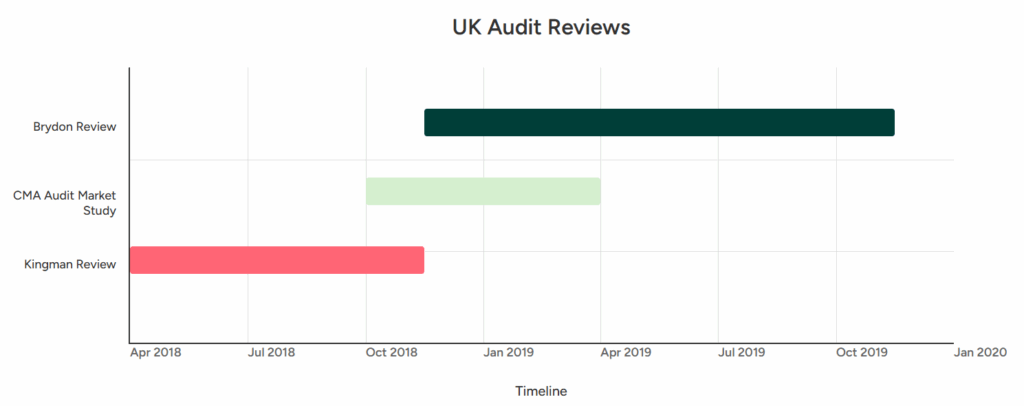

The collapses of companies such as Carillion, BHS and Patisserie Valerie prompted a trio of reviews into company audit:

The reviews converged on one general conclusion: existing audit and corporate‑governance rules were too narrowly focused. For the economy’s most important businesses, audit didn’t always deliver the trust and certainty needed by capital markets and the public.

When the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) published its Restoring Trust in Audit & Corporate Governance white paper in March 2021, it asked whether the PIE parameters should be widened “to increase the scrutiny of large unlisted companies.”

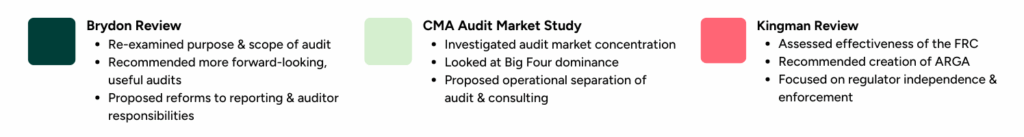

The consultation tabled two size‑focussed alternatives:

Respondents to the white paper were split. Roughly three‑quarters supported bringing large private companies inside the regime. But many feared the Wates’ test cast the net too widely, and 500/500 too narrowly. Many respondents argued that “public interest” should hinge on systemic or economic significance, rather than business scale alone.

The Government’s 2022 Proposal: the “750:750” compromise

When ministers issued their formal white paper response in May 2022, they opted for a middle path: any UK company with ≥ 750 employees and ≥ £750 million annual turnover will become a PIE. The future Audit, Reporting & Governance Authority (ARGA) will regulate these firms. To keep the burden “proportionate, there were some lighter‑touch exemptions. For example, excluding Lloyds Syndicates and removing some of the mandatory requirements for audit committees and auditor rotation.

The new threshold was expected to capture c. 600 additional companies—far fewer than the Wates’ test. But enough companies to cover most large corporates whose sudden failure could ripple through supply chains, workforces or pension schemes.

The government also proposed to reserve powers for ARGA to act in “exceptional cases” that fall outside these parameters when a matter is unmistakably in the public interest.

Baglan Bay Group: a public‑interest failure with no PIE status

Against the background of reform proposals, the 2021 liquidation of the Baglan Group in South Wales is a good case study. Baglan operated a private‑wire network supplying electricity to the 180‑acre Baglan Energy Park near Port Talbot, South Wales.

The Energy Park was occupied by several businesses, including Sofidel, one of the largest producers of toilet tissue. Importantly for local infrastructure, Baglan also provided electricity to local flood defences and waste-water treatment.

The Baglan Bay Collapse and Its Local Impact: why did it matter?

Liquidation is the most final of all business insolvency processes. The liquidator’s role is to realise the company’s assets for the benefit of creditors and formally close the business. It’s role is not to keep the business running, regardless of the impact that closure may have.

In the case of Baglan, closure meant terminating supply. It was argued this would threaten public health and environmental safety, along with hundreds of local jobs.

Government Intervention in a Non-PIE Entity

What followed was a battle between the liquidator, the Secretary of State for Business and the Welsh Government. The Welsh Government challenged the liquidator’s proposals to cease operations in court; they even commenced Judicial Review proceedings on the Secretary of State. Fortunately for businesses and citizens in the local area, a High Court ruling allowed the parties to reach a compromise. Supply was maintained until a contingency was put in place.

Despite the public interest in this case, the Baglan Group was not a PIE. It was unlisted with no securities on a regulated market. It was not a bank or insurer. The workforce and turnover figures fell short of the 750:750 trigger point proposed by the Government.

Nonetheless, stakeholders, including Ministers and the Court, treated the case as one of genuine public interest. The Secretary of State even issued an indemnity so that the liquidator could fund maintaining the essential supply.

Would PIE status have made a difference?

Whilst it is unlikely that PIE status would have made any difference to Baglan’s prospects for survival, the extra transparency and regulation might have surfaced earlier warning signs. Signs allowing the local Government or the energy regulator to intervene, before the situation became critical for stakeholders and costly for public finances to fix.

What Baglan teaches us about strict definition limitations

Public interest can be local rather than national. Baglan’s failure would not have shaken UK capital markets, but it could have plunged a regional business park and critical infrastructure into crisis—particularly if supply was disconnected and local flooding occurred.

Sectoral importance matters. Energy generation and distribution, like water, transport or digital infrastructure, can create public‑interest externalities, regardless of company size.

Regulatory agility is essential. Crystallising the public interest issues in the Baglan case at the point of liquidation created a huge amount of uncertainty for those relying on the electricity supply. Ultimately, taxpayers had to pick up the costs of mitigating the risks to business and the public.

Implications for the reform agenda

In July 2025, the Government announced that the draft Audit Reform and Corporate Governance Bill will not be published in the current session of Parliament. Instead, further consultation will be undertaken to refine the proposals. Consultations provide an important opportunity to consider further how extending the PIE definition to private companies could be achieved in a way that minimises regulatory burdens on businesses.

For entities like Baglan, where local consequences loom large, the Government and regulators may benefit from closer regulatory oversights from PIE status so risks surface sooner. One challenge of having more nuanced and objective criteria to classify a private company as a PIE, is how PIEs are identified from vast numbers of private UK companies.

However, a look at the Government’s Industrial Strategy gives a clear view of many of the key sectors for the economy, each one owned by a Government Department. It is not inconceivable that companies, whose failure could have systemic implications but currently aren’t classified as PIEs, are already known to those Government Departments.

So, when is a PIE not a PIE?

When a company sits outside the statutory definition, yet its collapse would still hit workers, suppliers, customers and citizens hard enough to require an extraordinary intervention.

The Baglan case, one of a number of insolvency cases where the Government has had to intervene to mitigate the effects of a collapse, reminds policymakers that public interest isn’t confined to balance sheets or listing status; it can reside in a single sub‑station, providing essential protections for a local community.

As the Audit Reform Bill continues to incubate with policymakers, we would do well to remember that the next “public interest” emergency may not look like a FTSE‑350 name at all. The challenge for the policymakers is to craft a regulatory framework that is robust yet nimble, anchored in clear thresholds, but capable of spotting a Baglan-type case before the power goes off.

What are your views on expanding PIE definitions? Join the conversation by contacting the CPIA or follow our ongoing research into audit reform.